In our present social, political, and spiritual distress—of which the church appears to be both a perpetrator and a victim—Christians are weighing their options for cultural engagement.

Rod Dreher has put forward The Benedict Option, which advocates for something like monastic retreat rather than transformative influence. In the same way that Benedict of Nursia withdrew from the culture wars in the declining days of the Roman Empire, Dreher proposes, Christians today need to build our own communities to preserve what is holy and sacred in faith and learning for the sake of future generations.

Others have responded to the current perceived crisis with various alternatives, both Catholic and Protestant. There is talk of the Wilberforce Option (sustained, principled protest), the Kuyper Option (recognizing God’s sovereignty over multiple spheres of society), the Dominican and Franciscan (in addition to the Benedictine) Options, and so on.

As educators who value Christ-centered liberal arts education, might we also consider “The Milton Option”?

Of Education

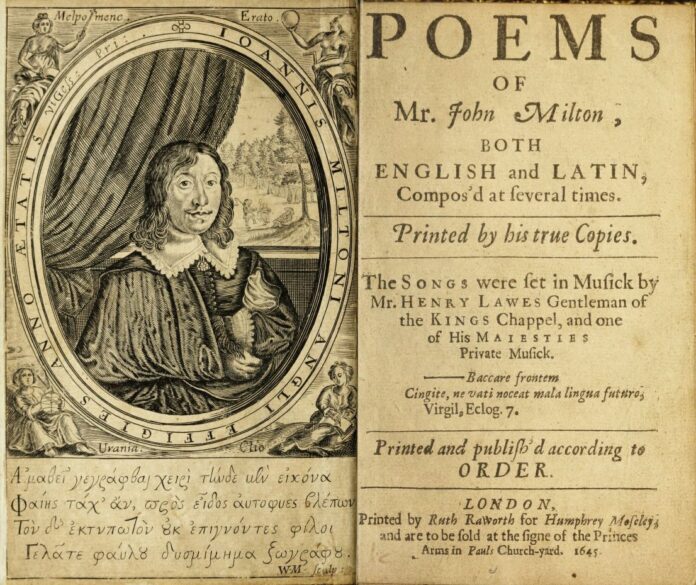

Writing in a time of political conflict and religious turmoil, Puritan thinker and epic poet John Milton—most famous for writing Paradise Lost—first composed in 1644 an influential essay entitled “Of Education.” There he argued that distinctly Christian education had a sacred purpose in the divine economy. “The end of learning,” Milton wrote, “is to repair the ruin of our first parents by regaining to know GOD aright, and out of that knowledge to love Him, to imitate Him, to be like Him.” In short, Christian education is a form of divine grace to heal a wounded world.

Milton called this way of learning a “generous” education, by which he meant a liberal education—one that was open-handed and liberating, leading to personal and spiritual freedom. And part of his argument was that such a liberal education would prepare a person for “all of the offices of life, both public and private, of peace and war.”

By “all the offices,” Milton meant the varied callings that we have in life. We are called to worship and ministry in the local church, as well as to be good neighbors, friends, and community members. We become, perhaps, to be husbands and wives, fathers and mothers. And we serve in diverse professions and marketplace vocations. A fully Christian education provides preparation for life in all its fullness—mind, body, soul, and strength.

Such an education is more necessary now than ever, when the challenges to offering a first-rate college education are manifold and increasing. These challenges are missional, social, financial, spiritual, intellectual, moral, and legal. To persevere will require a mentality nicely encapsulated in a few choice phrases from a besieged army in the Old English poem The Battle of Maldon: “Our hearts must be stronger, our purpose firmer, our spirit higher as our might lessens.”

A Cursory History

Christian educators found strength of soul in Christ-centered liberal arts long before John Milton matriculated at Christ’s College, Cambridge in 1625. So, where did this form of education begin?

Liberal education goes back to the ancient Greeks, of course, who were looking to develop leaders for a free and democratic society—leaders who knew how to think and argue, write and speak. To that end, the Greeks provided a comprehensive education (only to certain men, sadly, not women or slaves, as later become common in Christian education) in philosophy, art, music, mathematics, and history, while also exploring the natural world.

Christian liberal arts education is nearly as ancient. Already in cities like Alexandria and Antioch, where the Christian community was in the minority but played an increasingly influential role in civic life, early Christians who admired Greek learning sought to bring liberal education under the lordship of Jesus Christ. Their goal, in effect, was to produce leaders for the kingdom of Christ—the kingdom that held their highest allegiance.

Briefly told, liberal arts learning was codified by Martianus Capella in the early fifth century as the traditional seven liberal arts—the trivium (grammar, logic, rhetoric) and the quadrivium (geometry, arithmetic, astronomy, and music). Dorothy L. Sayers helped to re-popularize the artes liberale in the twentieth century through her famous essay “The Lost Tools of Learning.” A notable figure in this history is Alcuin, who served in Charlemagne’s court and in effect baptized Capella’s essentially pagan education by creating a school for distinctively Christ-centered, liberal arts learning. The trivium and the quadrivium formed the core curriculum throughout the Middle Ages, beginning in the cathedral schools and then expanding through the emerging European universities.

Liberal arts learning flourished in the Renaissance and therefore came also to have an influence on the Protestant Reformation. When the Florentine Reformer Pietro Paolo Vergerio described the type of education he prized for young Christian leaders, he said, “We call those studies liberal which are worthy of a free man; those studies by which we attain and practice virtue and wisdom; that education which calls forth, trains, and develops those highest gifts of body and mind which ennoble men to a lofty nature.”

In Germany and Switzerland, Luther and Calvin gave similar advice to parents who wondered how best to educate their children. “Although we yield the first place to the Word of God,” said Calvin, “we do not reject good training. The Word of God indeed is the foundation of all learning, but the liberal arts are aids to the full knowledge of the Word.” The famous Reformer went on to say that even a little bit of liberal arts learning goes a long way: “Men who have either quaffed or even tasted the liberal arts penetrate with their aid far more deeply into the secrets of divine wisdom.”

As the president of a Christian liberal arts college, I like to see students persist to graduation, transformed over four years by our general education curriculum. But—like Calvin—I also see the remarkable difference even a semester can make. By the time freshmen go home for Thanksgiving, their parents will be able to see how rapidly they are becoming more fully the women and men that God is calling them to become.

Our cursory history has touched Africa and Asia Minor before landing in Europe. But similar transformations take place whenever and wherever Christians pursue liberal arts learning that is grounded in the gospel. The 17th century Moravian reformer John Amos Comenius—who served God in war-ravaged, plague-ridden times—rightly began his Pampaedia (meaning “universal education”) by affirming his desire that through Christian education “not just one particular be fully formed into full humanity, or a few, or even many, but every single person, young and old, rich and poor, of high and low birth, men and women, in a word, everyone who is born: so that in the end, in time, proper formation might be restored to the whole human race, throughout every age, class, sex, and nationality.”

Comenius’s multi-ethnic vision for Christian education traveled also to the Americas. Writing from her convent in Mexico City sometime in the same century, Sister Juana Ines de la Cruz worried that “sheer love of learning” might distract her from the love of God. But she concluded that her love of the liberal arts, too, could be brought under Christ’s lordship. “All things proceed from God,” she reasoned, “who is at once the center and the circumference from which all existing lines proceed and at which all end up.” In short—for Christians on every continent—all truth is God’s truth, wherever it may be found, because in Christ all things hold together (Colossians 1:17).

For centuries this principle animated American higher education. It started at Harvard, of course, where the school’s founders—Puritan divines—stated their goal that every student should be “plainly instructed and earnestly pressed to consider well that the main end of life and studies is to know God and Jesus Christ and therefore to lay Christ in the bottom, as the only foundation of all sound knowledge and learning.”

The primary objective in those days was to graduate well-educated ministers. But soon the vision grew into something more kingdom-expansive. And as higher education spread from east to west, whether the new schools were Wesleyan, Baptist, or Presbyterian, they were nearly all liberal arts colleges that started with the classics and ended with moral philosophy. Christ-centered liberal arts learning was the dominant mode of American higher education into the 20th century.

A Necessary Example

Sadly, the liberal arts are coming increasingly under question. Distinctively Christian higher education has always had its detractors, of course, but today we hear a chorus of doubters from every direction. There are ceaseless questions about the cost of college and about job prospects after graduation. Enduring questions about the meaning of the good life have receded; practical economy is not merely ascendant, but regnant. For educators who love liberal arts learning in the Miltonic tradition, it feels like a crisis.

Richard Hughes Gibson—who teaches English literature at Wheaton College—finds the perfect remedy in the extraordinary school that Cassiodorus developed in southern Italy in the sixth century. In a sparkling essay he wrote for The Plough Quarterly in September 2020, Gibson advocated for “The Cassiodorus Necessity: Keeping Faith Alive through Christian Education” (not merely an option, notice, but a necessity, because without a Christian intellectual culture we are unable to weigh our options at all).

Like Benedict of Nursia, Cassiodorus lived at a time of social unrest, military conflict, and imperial collapse. He left behind his high public offices in the Roman Empire and returned to his native Squillace (in what today is known as the toe of the Italian boot), to build up what he called “the Vivarium”—a life-giving community for Christian liberal arts learning. The Vivarium included a classical library and a scriptorium for copying learned manuscripts.

According to Gibson, although sacred Scripture was the center of Cassiodorus’s education vision, it was not its limit. His two-volume magnum opus—The Sacred and Divine Institutes—covered geography, astronomy, logic, rhetoric, mathematics, and history as well as theology and biblical studies. Essentially, The Institutes was a complete curriculum for Christian liberal arts learning.

This curriculum self-consciously stood in what was already a venerable intellectual tradition by the 6th century: Cicero, Quintilian, Aristotle. Rather than commending his own insights, Cassiodorus wanted to commend “the words of the ancients, which are rightly praised and gloriously proclaimed to future generations.” But he wanted to do something more than preserve the learning of the past; he wanted to promote a thriving Christian intellectual culture. “When I became aware of the fervent desire for secular learning,” he wrote, “through which a great multitude hope to obtain worldly wisdom, I was deeply grieved, I confess, for while secular authors without a doubt have a powerful and widespread tradition, the Holy Scripture wanted for public teachers.” Cassiodorus thus lamented the lack of public Christian witness, which he believed could be strengthened by bringing liberal arts learning under the lordship of Jesus Christ.

The impulse to preserve the learning of the past—which we see promoted, for example, in the Benedict Option—is a noble one, as is the ambition to bring every thought captive to Jesus Christ (2 Corinthians 10:5). But Cassiodorus, Milton, and other champions of the integration of faith and learning would urge us to pay equally urgent attention to the spiritual, intellectual, and social needs of our own time and place.

God is calling us to do something other than retreating into our own embattled communities and something beyond simply transmitting a valuable tradition to the rising generation. He is calling us to make new discoveries and to disseminate the best of Christian learning, while at the same time answering the toughest questions people are asking today. He is calling us to share, not just to save, and in this way to have a positive influence on the academy, the culture, and the world.

Of Vocation

Liberal arts education is in measurable decline. There are more than 5,000 colleges and universities in the United States. A recent update of David Breneman’s landmark 1990 study sought to document how many schools remain committed to a distinctively liberal arts curriculum. There were 212 such liberal arts colleges in 1990. As of 2010 there were only 136. Doubtless there will be fewer still by 2030, given the disruptive changes we are witnessing in higher education.

There is ample room across the educational landscape for other kinds of schools—community colleges, technical schools, research universities, and the like. But to educate leaders of the highest caliber and to prepare Christian men and women to make a difference in the world for Jesus Christ, Christian liberal arts education remains uniquely strategic. This mission is something to invest in and to advocate for.

One of the ways we champion liberal arts learning is by communicating its valuable connection to vocation. As we know from reading Ecclesiastes, from pondering the parables of Jesus, and from heeding the exhortations of the apostle Paul (e.g. Colossians 3:23-24), doing good daily work is a huge part of every Christian’s calling. And John Milton, for one, did not hesitate to say that a liberal education provided first-rate preparation for the world of work.

Prospective students and their parents need to know that one of the best ways to prepare for their career callings is by pursuing a liberal arts degree. Studies repeatedly show that many of the hallmarks of liberal arts education—reading, writing, creating, collaborating, thinking, analyzing, and problem solving—develop skills that are in high demand in the marketplace.

Some of the highest dividends on a liberal education are long term. A more specialized undergraduate degree may well help a student get a particular job more quickly. But given the multiple job changes that most graduates will experience over the course of a lifetime, eventually they will need the kind of intellectual flexibility that liberal arts learning is perfectly designed to foster. They will also find themselves on a long-term leadership trajectory in their chosen endeavors. There may be good educational reasons why liberal arts graduates are disproportionately represented among—for example—the CEOs of Fortune 500 companies. There are also habits of mind and moral virtues that help to explain why graduates of Christian liberal arts colleges typically have a profoundly positive influence on their churches and other Christian ministries.

Choosing the Milton Option does not exclude vocational considerations; it includes them. But it does so without making a career the exclusive or even the primary focus of higher education. Life is more than work, as Ecclesiastes also teaches us. “What does it profit a man,” Jesus asked, “if he gains the whole world and loses his soul?” (Mark 8:36). Liberal arts learning nurtures the soul by helping students understand why everything in a God-created, Christ-redeemed, Spirit-renewed world matters, including their daily work.

Liberal Arts Forever

Unfortunately, liberal arts learning is not inexpensive. In fact, it requires increasingly precious resources, especially when students and teachers live, study, and worship together in residential communities. Cassiodorus’s Vivarium and Milton’s Cambridge both afforded scholars the very best learning tools that the world then had to offer. In order to develop the best minds, they needed well-preserved books and well-appointed buildings in a setting that promoted both quiet reflection and scholarly colloquy.

Christians are making similar investments in higher education today, with similar aims. Simply put, Christian higher education is not a consumer good but a philanthropy. Thus, it has always required generous giving and sacrificial endowments from the people of God, including wealthy patrons like Cassiodorus. What makes these costly investments worthwhile is the intellectual, spiritual, and social transformation that takes place in the lives of students during their time at a Christ-centered, liberal arts college, and then afterwards the difference they make in the world for Jesus—the unique contribution that only someone with their gifts, convictions, and also educational opportunities can make.

At a time of social upheaval, when democracy itself is threatened and doubt is cast on the value of a college degree, some Christian colleges continue to choose the Milton Option—an increasingly counter-cultural option that because of its scarcity today may hold a brand advantage in admissions and enrollment. These schools promote liberal arts learning that honors the pre-eminence of Christ, prepares their students for all of life’s callings, and produces lifelong learners.

This form of education is nearly two thousand years old. It has survived any number of wars and revolutions, natural disasters, global pandemics, economic downturns and financial collapses, periods of persecution, and other crises and calamities. By God’s grace, it will endure until the day that Milton wrote about in his Animadversions upon the Remonstrants—the day he longed for—when the “Prince of all the kings of the earth” will don “the visible robes” of his “imperial majesty” and make his creation new.

Why do we pursue and promote Christian liberal arts education? If for nothing else, we choose it for eternal joy in the presence of the Lord and Savior who is both the source and the goal of all knowledge and truth.

This essay was strengthened by the valuable input I received from Jeffry Davis, Richard Gibson, and Karen Lee—colleagues at Wheaton College.